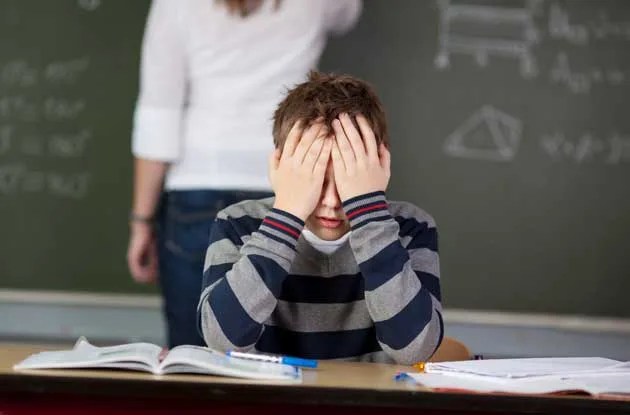

Many kids refuse to go to school when the first day comes around, but for some, it may be more than back-to-school anxiety.

Not every kid perks up at the thought of concluding his run of carefree summer days by returning to the classroom. Still, not every kid exhibits major defiance or stages a meltdown when confronted with the return. Has your child ever responded to this shift in routine by vocally or physically asserting her refusal? Has he clung to your legs or refused to get dressed in the morning? If so, your child may be suffering from school refusal, an anxiety-based disorder present in approximately 10 percent of school-aged children.

While many children exhibit school refusal behavior, not all are doing so consistently to the point where they are racking up absences and parents are in danger of losing their jobs. Amanda Morin, a parent advocate, former teacher, and education writer for Understood.org explains the difference between the summer slide and a more serious condition. Summer slide has a multitude of meanings, though it often refers to a loss of academic skills as well as difficulty sliding back into school routines. While a regular summer slide might include these two issues, a child with learning or refusal issues will have a more pronounced summer slide. These children will be unable to remember the positive aspects of school while also failing to regain skills and readjust to the routine.

School refusal is often connected to a school-centric issue, making it a common occurrence among children struggling with learning disabilities or learning and attention issues. “They have a higher incidence of refusal because they’re trying to get away from something that feels bad to them, or avoiding uncomfortable social or academic interactions,” Morin explains. This problem is amplified in children who have unidentified learning issues. Younger children will exhibit refusal behaviors because of an inability to articulate what it is that they are uncomfortable with. The key, Morin says, is digging deeper.

RELATED: Find Services for Children with Learning Disabilities

Recognizing the Problem

Many parents are apprehensive when it comes to having their child evaluated for a learning or attention disability or issue. Part of the stigma is saying, “I’m doing everything I can and it’s still not working,” Morin says. Parents often feel a personal sense of failure as well as a fear of labeling their children. Morin often counters this fear by explaining, “labels are for folders and not for kids. The label is the diagnosis that gets you the support to make sure that your child can thrive in school and be successful.”

Timing is another element parents struggle with when it comes to evaluation. Morin finds there is no universal right time, saying the right time is instead when the issue is clearly impacting your child’s functionality. “If you can’t get your child in the door, if he’s so anxious that he can’t sleep, if you’re concerned because your whole day is centered around talking to the school or getting your child out the door, if you’re worried you’re going to lost your job, if your child is just an anxious ball of fear, that’s the time to get help,” she says. While there is no exact right time, Morin also recognizes that sooner is usually better, since “the earlier kids have intervention, the more likely they are to become really successful down the line.”

Creating a Support System

Once you are concerned enough to seek help for your child’s issues, the first step is to stay calm and rational. While it’s very easy to blame the child or try to reason with them, it’s ultimately ineffective or even detrimental. Encouraging or pressuring your child by saying things such as, “you know you love school,” “you need to get out the door,” or “I’m going to lose my job,” will not help solve the root of the problem. You must keep in mind that it’s “not a negotiation,” Morin says, and that “your child’s anxiety is real.”

The next crucial step is to sit down and have a conversation with your child. You’ll want to discuss how you can make his transition back to school easier and remind him of the positive aspects. You’ll want to ask her what is worrying her, leaving the question as open-ended as possible. Morin finds that though some kids may be able to answer and some may not, the less you ask it as a leading question, the better answer you’re going to get. While it’s easy to say, “Are you worried that your teacher is going to be mean?” it’s much more effective to ask, “Is there something more specific that’s worrying you that we can talk through?” Continuing to check in with your child will ensure that he is receiving the support he needs until he is ready to ask for it himself.

A support system is one of the most important tools for both children and parents. “As parents, we don’t want to admit that we have weaknesses and we need support, but it’s definitely a team effort to get that kid back in the door to school,” Morin says. Perhaps the first person you should consult, besides your own child, is his pediatrician. It’s extremely important to make sure this anxiety or depression isn’t linked to an actual physical illness before proceeding.

Next, parents will need to discuss setting up an evaluation with the school. If your child has a learning issue or suspected disability that is impacting her education, the school has a legal obligation to do a free evaluation. Once the issue has been properly identified, parents and school staff can work toward providing the child with the support he needs, whether that be an IEP or 504 Plan, an outside counselor, or an informal support team.

It is also important that the parent feel as supported as possible. For this, Morin recommends parents join communities such as Understood.org, where they will have the “opportunity to speak to each other and understand that they’re not alone.” Morin finds this to be a wonderful resource for both the parent and child because “if you know you’re not alone, you can help your child know that he’s not alone as well.”

RELATED: Managing Your Emotions After Your Child’s Special Needs Diagnosis

Continuous Support

For the ongoing support of your child, it’s crucial to build a strong teacher-parent relationship. Keeping good contact with the teacher will allow parents to stay aware of progress or roadblocks as well as prepare for what is coming next. These relationships can oftentimes feel uneasy due to a mutual fear of inadequacy. “Nobody wants to feel like they’re doing a bad job at helping the child,” Morin explains. “Understanding that everyone is really trying to do the best they can is a really good way to start that relationship.” While parents and teachers should be respectful of each other, they should not be afraid to share concerns and advice so everyone around the child is on the same page. Instead of growing defensive, Morin says, parents and teachers must realize “the whole job is to raise the child up, that there’s this kid in the middle and we’re circling around him to make sure he’s going to be ok.”

While there are many plans and programs in place to help a child struggling with learning issues or school refusal, parents should remember it’s not a quick or easy fix, but rather a gradual process with little successes along the way. “I think it’s really important to let your child know he’s not lazy, he’s not stupid, he’s not unmotivated, he’s just thinking differently,” Morin says. “He thinks differently and everybody around him needs to learn to help him use the way he thinks to be really successful.”

RELATED: Find Special Needs Support Services Near You