A Long Island mom and author of a 10-year-old boy who has autism shares tips on how to help classmates, typical siblings, family, and friends understand autism, and how to stay positive in the process.

As mom to a 10-year-old with autism, Lyn Fontinell of Shoreham says one of the biggest misunderstandings about kids on the spectrum is that they don’t feel things the way other kids do. Fontinell remembers one incident when her son Frankie was playing with a group of young children: “Don’t worry,” one child said to another, “You can throw rocks at him and he won’t do anything—he doesn’t understand.” Fontinell was heartbroken. “What people tend not to realize,” she says, “is that their affect may be off, they may laugh at inappropriate times, but they feel hurt just like everyone else does, and they understand way more than people think.”

Underneath his disability, Fontinell says, Frankie is a kid who loves cheeseburgers,

|

|

Legos, and video games, just like many of his peers. “I started thinking ‘How can I get these kids to understand him and connect with him without seeing those outside issues?’,” she says. The answer, for Fontinell, was to write a book about it. Hi, My Name is Frankie, published in July, explains autism in a simple way that kids in grades K-2 can understand. The 30-page book features the illustrated version of Fontinell’s son, Frankie, and follows an interactive format in which the narrator asks the reader questions. The main character’s autism is revealed at the end of the book. “I wrote the book as if Frankie was talking to a friend,” Fontinell explains. “My goal is to have children begin to understand that what they may see as different is very much the same underneath.”

In April, during Autism Awareness Month, Fontinell helped bring a special program to Miller Avenue School, where Frankie is integrated into a typical classroom. During gym class, students in second through fourth grade visited five ““sensory stations” that helped them experience the world like an autistic child. At one station, the children put on headphones blasting loud music and tried to answer questions. “This is how some children with autism feel because they can’t separate background noise,” Fontinell explains. At another station, the kids wore burlap bags on their arms and were asked to imagine how it would feel trying to do their math homework while their skin was so itchy and irritated. “By the end of the class, they didn’t want to leave,” Fontinell recalls. “Frankie came in and they all just wanted to talk to him. I almost cried watching it. They just needed to understand—that’s what it all comes down to: information, understanding, acceptance.”

Here, Fontinell offers insights and advice for other parents of kids with autism.

| How can parents of children with autism help their child’s classmates and friends better understand autism? Kids are going to be curious and ask a lot of questions—try to put things simply and teach them about it in a way they can grasp. Give them something they can relate to so you don’t lose them. Instead of using terms like “auditory processing,” explain it like this: “Imagine you have a big wad of gum in your mouth and you want to say something but you can’t get it out. That’s how an autistic child might feel, and they might get frustrated or upset, which causes them to act out.” Explain that underneath their different behaviors, kids with autism are exactly the same as they are. Even if they’re not looking at you, they hear when you talk to them, and they understand more than you think. They have likes and dislikes, things they’re interested in, and they have feelings just like you do. How do you deal with adults who don’t understand Frankie’s diagnosis? Frankie has three older sisters—what advice do you have for parents who also have typically developing children? There’s no easy road when raising a child with autism. How do you stay positive? |

Also See:

- Do’s and Don’ts of Mainstreaming Your Child with Autism

- How an NYC Mom is Managing Mainstreaming Her Gradeschool-Aged Son

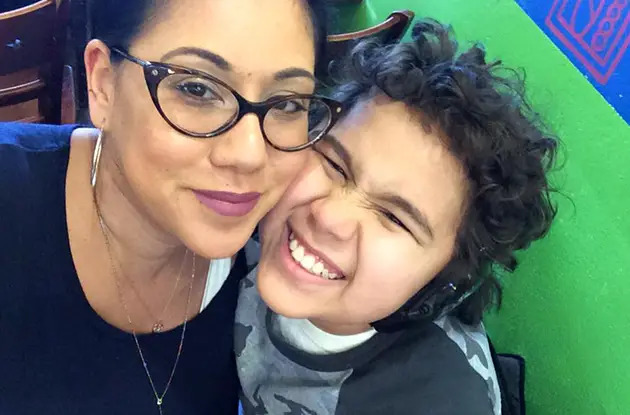

Author Lyn Fontinell with her son, Frankie

Author Lyn Fontinell with her son, Frankie