Research on autism show how it may be linked to epilepsy and how it affects behavior. An NYC specialist investigates the connections among autism, epilepsy, and behavior, and shares what can be learned from these links.

Until Gianna Ferrari was 2½, her parents, Bernie and Jillian, didn’t notice that their little girl wasn’t behaving quite like other toddlers her age. Because Gianna had kidney and urinary tract problems, the Ferraris, who live on Staten Island, stayed focused on her medical issues. Then Gianna’s baby brother, Anthony, came along.

By the time Anthony was 6 months old, the differences between the two children became glaringly obvious. Anthony seemed to comprehend his parents’ language. Gianna still didn’t. Anthony was beginning to play with baby toys. Instead of playing with toys, Gianna obsessively lined up DVDs. She would stare into space for minutes at a time, as if she saw something no one else could.

As a teacher, Jillian had taught a first-grader with Asperger syndrome, a high-functioning form of autism. She felt that her daughter’s behaviors were similar to his. A psychologist sent by their local school district diagnosed Gianna as having pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), another subtype of autism. But the exam seemed rushed, and the Ferraris had their doubts.

To get a second opinion, they took Gianna to the Developmental Neuropsychiatry Program at Columbia University Medical Center, a member of the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network.

There, specialists extensively evaluated Gianna using interactive interviews and

behavioral evaluations, as well as physio-logical and genetic tests, and ultimately confirmed that Gianna had autism.

In the months that followed, Gianna began behavioral therapy five times a week at home. She also began speech therapy and enrolled in a preschool that provided additional early-intervention services.

Jillian quit her teaching job to work with Gianna at home and coordinate her therapy appointments. Then, as Gianna neared her 5th birthday, one of her therapists noticed her tendency to stare into space. She raised the possibility that Gianna might be having seizures.

One of Gianna’s doctors in the DNP referred her to another specialist within Columbia’s ATN center—pediatric neurologist Reet Sidhu, M.D. Dr. Sidhu conducted an overnight electroencephalography—a noninvasive test that uses a head cap studded with electrodes—to measure Gianna’s brain activity. The EEG showed that Gianna had “epileptiform discharges”—abnormal brain activity similar to that seen in epilepsy.

Though epileptiform discharges can predispose people to seizures, they’re not inevitable, Dr. Sidhu told the Ferraris. Gianna fell into this latter category. Her staring was not due to seizures, but her EEG was clearly abnormal.

“We know that children with autism spectrum disorders have a higher risk of epilepsy,” Dr. Sidhu explains. “But what is not entirely clear is the relationship of abnormal epileptiform discharges to behavior, and what to do with those children who have abnormal EEGs but have never had any clinical seizures.”

How Autism and Epilepsy May Be Linked

An estimated 10 to 30 percent of people on the autism spectrum have epilepsy with obvious seizures. As many as 60 percent of individuals with ASD have epileptiform discharges on EEG but have never had a clinical seizure.

Dr. Sidhu’s research focuses on studying the relationship between abnormal EEGs and behavior in this group. (Her interest in this area dates back to childhood: Her younger brother, now 36, has autism and has suffered from seizures his entire life.)

Given the frequency of epileptiform discharges in people on the autism spectrum, she and others wonder whether they might contribute to autism symptoms and related behavioral problems such as attention and mood.

“In the past we would never consider treating anyone with anticonvulsant medication unless they actually had a seizure, but we are now rethinking this notion,” Dr. Sidhu says. “The answers are not clear-cut. But what an exciting thought to potentially have a treatment option for some of the problem behaviors that are so challenging for these children.”

In 2011, Dr. Sidhu began collaborating with neurologists at other Autism Speaks ATN sites such as Vanderbilt University and Massachusetts General Hospital. Together they are studying the effects of abnormal EEG activity such as Gianna’s. The research is being funded by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration through Autism Speaks Autism Intervention Research Network on Physical Health.

For the multi-site study, researchers recruited 60 children with autism, ages 3 to 7, who had no known cause for their autism and had never had any seizures. In particular, the team is looking at how EEG abnormalities relate to daytime behaviors such as attention and aggression.

“This public-private partnership between Autism Speaks and HRSA has provided critical funding to investigate key areas of medical concern, including epilepsy, among parents of children with ASD,” says Autism Speaks vice president of clinical programs Clara Lajonchere, Ph.D. “Given the high rates of epilepsy among children and adolescents with autism, it’s imperative that we can quickly translate the results of well-designed studies into safe and effective treatments and interventions for these individuals.”

Further Research on Autism and Epilepsy through Autism Speaks ATN

For Dr. Sidhu, being part of the Autism Speaks ATN means she can tap into what she calls an “engaged and versatile community of researchers and families,” both at Columbia University and across North America. She now co-chairs the ATN’s Neurology, Genetics and Metabolics Committee, which includes experts in pediatric neurology, genetics, metabolism, sleep, and developmental pediatrics. All of the members are both practicing clinicians and researchers collaborating on studies that cut across their related fields. Together they are creating evidence-based guidelines to provide a standard of care in the neurological workup of autism spectrum disorders.

“Our goal is simple: to improve the clinical care of our children with autism,” Dr. Sidhu says.

Dr. Sidhu’s role in the ATN allows her to be a part of the international effort to advance understanding of the connection between autism and epilepsy—while also directly helping families grapple with this and related neurological issues.

With the Ferraris, for example, Dr. Sidhu recommended against putting Gianna on seizure medication, since she wasn’t having true epileptic seizures and the drugs have side effects.

Instead she suggested that Gianna continue to receive autism intervention services for her behavioral issues, while returning for follow-up neurological exams two or three times per year. At these exams, Dr. Sidhu observes Gianna while she plays, asks her to run in the hallway, checks her reflexes, examines her eyes, and measures her head. Gianna’s mother signs a waiver allowing Dr. Sidhu to use the test results in her research.

“If they can be helpful for someone else, that’s great,” says Jillian, who looks forward to the day when researchers can provide more answers—and treatments—for the neurological problems so often associated with autism. Meanwhile, she actively maintains a Facebook page, Jillian’s Special Needs Family, which she loads with resources, advice, and encouragement for families going through similar experiences.

How Research on Autism and Epilepsy is Helping Families

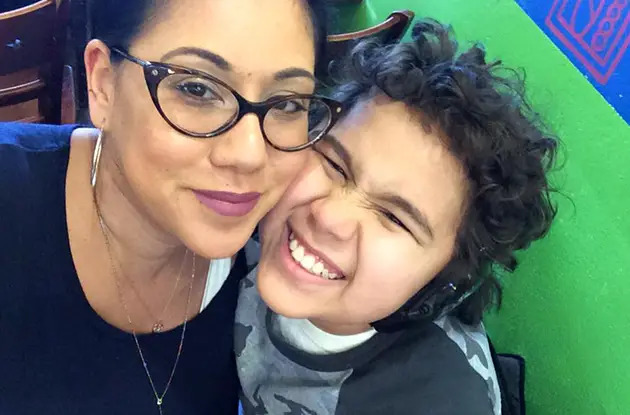

With the support of her family, classmates, and therapists, Gianna’s social life is progressing. Now 7½, she takes dance lessons and is a Girl Scout. She attends classes at a special education school during the week and enjoys several one-on-one sessions with therapists after school. She is learning to read and can count coins and tell time.

On Saturdays she attends Kids Connect USA on Staten Island. The program enables kids on the autistism spectrum to socialize with their normally developing peers. Gianna particularly loves the program’s arts and crafts and playing board games with her new friends.

Gianna still has tantrums on an almost daily basis. She also lacks awareness of everyday dangers, and so requires continual supervision. But these challenges used to be far worse, says her mom, who credits Gianna’s behavioral therapy and anti-anxiety medication. “She’s better able to communicate her needs now, which helps us eliminate the tantrums.”

At the same time, her parents report that each visit from the behavioral therapist brings noticeable improvements. Dr. Sidhu and her staff have noticed the improvements as well. The first time Gianna visited their office, she hardly spoke. In follow-up trips, she screamed, “I want to go!” over and over again in the waiting room and would endlessly repeat the phrase “How are you, Dr. Sidhu?” in the exam room.

A year and a half later, Gianna is speaking politely, cooperating with her doctors, and engaging less in repetitive behaviors during her visits.

“Her anxiety has clearly improved over time with the help of behavioral interventions,” Dr. Sidhu says. “The Ferraris embody such great attributes of a family dealing with a child with a disability because they are so dedicated, so willing to do everything for Gianna, and they handle all adversities with such grace,” Dr. Sidhu continues. “They make it seem almost effortless in some ways. I am fortunate to be part of the care team for Jillian and her family.”