In hopes of gaining a greater understanding of how the brain works, Manhattan-based organization, the Child Mind Institute advocates more scientific research of children with learning disorders and psychiatric disabilities. The organization believes that more studies could lead to more accurate diagnosis and treatment.

The Child Mind Institute, a Manhattan-based organization, is a vocal leader in advocating for more scientific research on children and adolescents with psychiatric and learning disorders. Beyond the goal to find better ways to help this population, studying early development promises to offer clues about the progress of development throughout the lifespan.

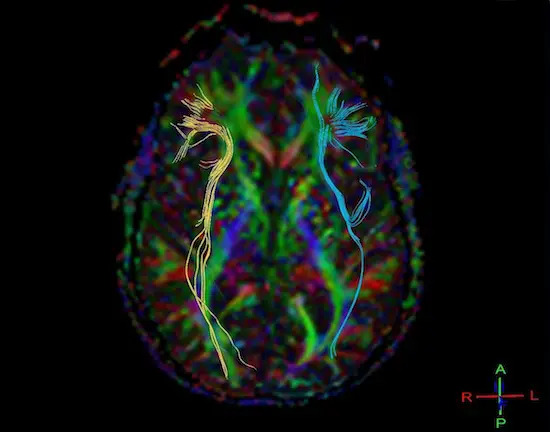

Because researchers and clinicians at CMI and other mental health organizations want to understand how the brain works and how it sometimes doesn’t work, studying children is indispensable. Some 75 percent of psychiatric and learning disorders manifest before age 24, and 50 percent before 14. Severe developmental disorders make their mark on the brain before birth.

So the pediatric population is indispensable, but it’s also notoriously difficult to study. Parents are understandably wary of enrolling their kids in studies and clinical trials. The result: Samples used in research are so small that the results are often questionable and yield too few data sets (such as fMRI images, patient histories, and genetic data that can be analyzed by computer to reveal links between biology and behavior).

Just imagine how difficult it can be to get young children into magnetic resonance imaging scanners—and staying still long enough—to gather brain images that could, together, reveal the biological basis of ADHD, say, or autism. “It’s really hard getting these data sets,” says Michael Milham, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Child Mind Institute’s Center for the Developing Brain. “You do the math, and it’s ridiculous.”

10,000 Heads Are Better Than 1

One solution is “open science”: sharing data freely with other researchers around the world in order to make the most of a limited resource—sort of a “10,000 heads are better than 1” situation. Dr. Milham spearheaded a project that aims to do just this, called the Healthy Brain Network, which facilitates the sharing of data and analytical tools. It also encourages non-traditional investigators, like computer scientists and statisticians, to tackle the difficult and exciting problems of teasing meaning out of the data collected.

This collaboration is the future of brain research, much as it was a defining part of the Human Genome Project and other large-scale efforts before it. “People from outside the whole biomedical enterprise are starting to get heavily involved in it,” says Cameron Craddock, Ph.D., director of imaging at CMI. “And ever since their inclusion, it’s definitely increased the rate at which things are being solved. Things are happening.”

But sharing will only get researchers so far without bigger and better collections of data. This is another area that Dr. Milham is engaged in, and his best hope is clinical-research integration—turning patient information into valuable (and anonymous) data for researchers.

“As long as clinical and research stay in their separate bubbles, we have a problem,” Dr. Milham says. “Massive amounts of information is all lost, just sitting in file cabinets.”

He is referring to data collected by treating clinicians—data about case histories and informed treatment decisions—that is not available to the researchers which might tell a larger story. Dr. Milham believes that if clinicians and researchers develop a culture of working together and sharing quality data across this traditional divide, the pace of discovery will increase.

To that end, the Child Mind Institute is developing an electronic medical record system that will collect relevant anonymous data in a format that can be used by research scientists if patients and families consent. This EMR strategy has been effective at increasing databases and driving discovery in other fields, from rheumatology to medical genetics to multiple sclerosis, and Dr. Milham hopes the CMI project will inspire mental health clinicians across the globe to join in.

“In an ideal world you’d link together a bunch of EMRs across different sites and you can go and do these large-scale data-mining analyses,” he says. “This is a very economic way, frankly, of generating the data we need to come up with initial ideas or guesses that we can follow with clinical trials.”

Behind the Data

But what are the goals? What can the interdisciplinary study of massive amounts of imaging, genetic, and behavioral data tell us about the brain in general and young people who struggle with emotional, behavioral, and communication deficits in particular?

We can begin by improving our current understanding of mental illness, which is based on diagnoses that are essentially groupings of symptoms.

Dr. Craddock offers an example of

the frustration with the current diagnostic system: “Take depression, for example. In order to be diagnosed

as clinically depressed you need to have five of nine symptoms. So what it means is, you can have two people who both have a diagnosis of depression but they only have one overlapping symptom.

Those people are very different.”

By looking closer at these cases, by gathering more detailed and more reliable data about all domains—behavior, biology, imaging, cognition—we may be able to divide current diagnoses into smaller, more homogenous groups that are more clinically helpful.

Subdividing diagnoses is useful, Dr. Craddock says, because one group may benefit from a particular treatment while another group benefits more from a different treatment.

This is incredibly important, he says, because even if you have an accurate diagnosis, whether or not a child will respond to a particular medication or therapeutic intervention recommended for his disorder can be difficult to predict. “If we could come up with a biological signature that could better identify a subpopulation of a disorder, or could better prescribe the appropriate treatment, or could predict the outcome of different medications,” Dr. Craddock says, the impact could be real and transformative for young people.

He and Dr. Milham have already made strides in this direction, including the ADHD 200 competition, a project in which interdisciplinary researchers were able to in some cases correctly identify not only ADHD diagnoses but also ADHD subtypes using only MRI data. The competition was part of a larger effort to share data and draw interest from a wide range of researchers, under the larger umbrella of the Open Neuroscience Initiatives sponsored by the Child Mind Institute’s Healthy Brain Network. Other initiatives include the Autism Brain Image Data Exchange.

To get to wide clinical applicability, however, we need more data, more bright researchers, more sharing, and the willingness to engage these difficult problems. Dr. Craddock concludes: “Our goal is to be able to map the trajectory of a normal developing child so that we can identify earlier in their life when they deviate.”