How do you know whether your child is receiving quality math and science education in school? Insideschools, which provides authoritative, independent information about New York City public schools, shares what to look for when sizing up your child’s learning environment.

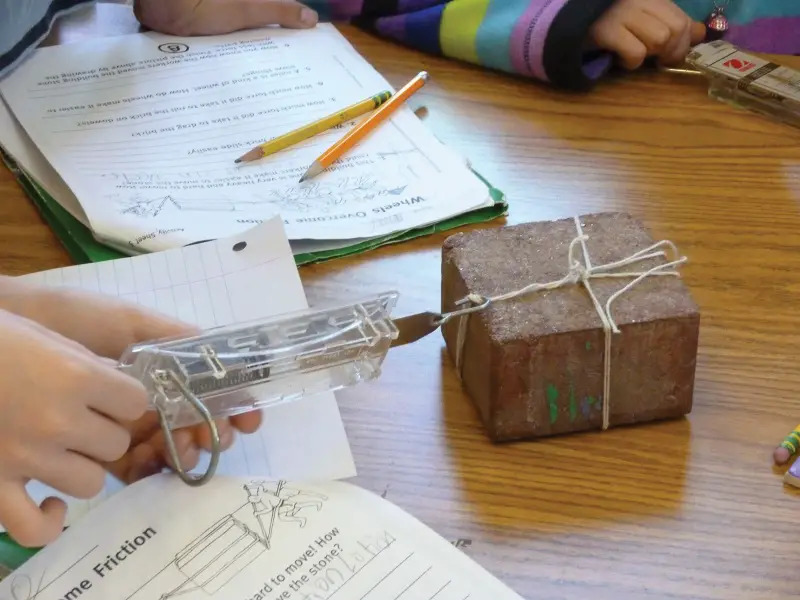

Real science investigations can spark curiosity and make kids want to do more.

Are you confused by your child’s math homework? Are you worried that the work seems too hard—or too easy? Is science an afterthought in your child’s school? This two-part guide will help you find out whether your children are getting the math or science instruction they need in pre-kindergarten through fifth grade—and will help you do something about it if they aren’t. It will explain what the new Common Core State Standards mean for your child.

No school is perfect, but if you understand the strengths and weaknesses of your child’s school you can help fill in the gaps—even if you don’t know much math and science yourself. You can learn a great deal by looking around your child’s classroom, by asking your child’s teacher a few questions during a parent-teacher conference, and by listening to your child talk about his day.

In this section we will focus on how you can make the most of your next visit to your child’s school. You’ll likely be there for an open house or other early-fall meet-and-greet this month, so arm yourself with the ideas below.

The knowledge and insights found here are the direct result of a project undertaken by Insideschools.org, a project of the Center for New York City Affairs at The New School, with generous support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. School data was reviewed and analyzed to identify New York City public schools that were strong in math and science. Through visits to the top schools, “test prep factories” were weeded out, and our reporters began to see similarities among our favorites. Additionally, we looked at research and spoke to experts in the field—as well as teachers, parents, math and science coaches, and administrators—to define what constitutes strong math and science instruction in elementary school. While the project took place in New York City, the conclusions drawn are relevant to schools in any district in our wider region.

Math and Science Guidelines For All Grade Levels

Whatever your child’s grade level, look for fun-to-read books about math and science, as well as fish tanks, animals such as gerbils, live plants and tools including magnifying glasses, magnets, or electrical circuits. There is more to math and science than what you can find in a textbook.

|

Your discoveries about the quality of your child’s math and science education will help you fill in the gaps—even if you don’t know much about math or science yourself. |

Check the daily schedule, which is usually posted in the classroom. Children should be working on math at least 1 hour a day. Science lessons should be part of a regular school day, not only a special class once a week. If you see an egg incubator (so children can watch chicks hatch and grow) or caterpillars (which will grow into butterflies), that’s a good clue that science lessons are part of the daily routine.

The best schools find ways to weave science together with math, reading, social studies, and even art. Children may work for long periods on units about birds, or bridges, or Central Park. Look for evidence of these explorations in the classroom. At PS 321 in Brooklyn, for example, kindergartners study trees. They post tree graphs, leaf rubbings, and diagrams based on their frequent trips to the park to observe changes over the course of the year.

Of course you want to see children’s artwork and essays on the walls, but you should see examples of math and science as well. At PS 221 in Queens, a bulletin board had fourth-graders’ own questions about science: “How do snails breathe?” and “How does dust form?” and “What started the Black Death?” Science exploration that starts with children’s own questions is more likely to prompt them to ask more.

Most of the science experts we interviewed said it’s more important to spark children’s curiosity than to develop a particular body of knowledge in the elementary school years. Whether your child is studying the solar system or rocks and minerals, it’s important that he is excited and engaged in his work. Learning lots of facts can wait.

“Too much rote learning may well kill interest,” said Richard Seager, a climate scientist at Columbia University and parent of two children who attended PS 75 in Manhattan. “I would think that the best that can be done is to instill a sense of wonder and interest in the natural world in the kids, that they may be motivated to pursue it more in the future.”

Math is a little different. It’s important for math to be exciting and fun. But there are also specific skills children need to learn each grade in elementary school to prepare them for middle school and high school. A look around the classroom will also help you discern if these skills are being taught.

Math and Science Guidelines for Pre-Kindergarten and Kindergarten

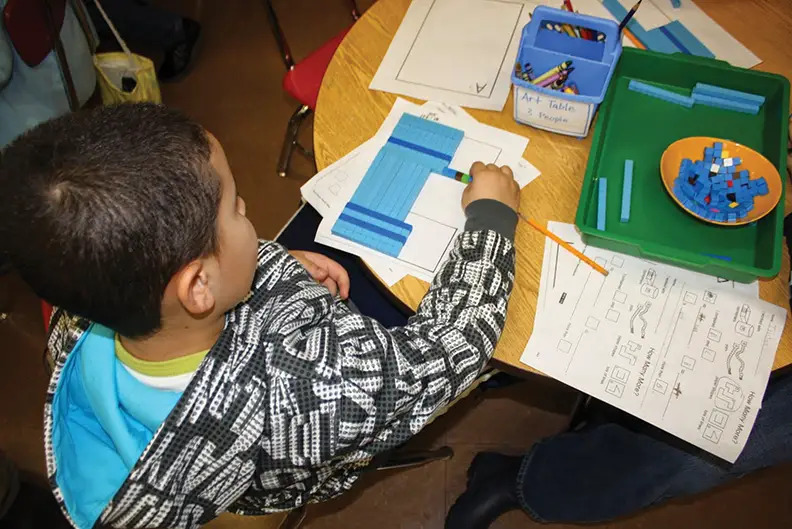

Small counters, puzzles, and blocks help kids make sense of how math works. |

In pre-kindergarten and kindergarten, look for blocks and puzzles. Research shows that developing good spatial skills by learning how to put together different shapes is just as important to understanding math as learning to count.

You should look for small objects (such as buttons, plastic animals, or Legos) that children can touch, count, and sort. Even before children learn to write numerals, they need to get a sense of what numbers are. Counting objects builds an intuitive feel for math that teachers call “number sense.” Young children with good number sense quickly figure out amounts—who has more strawberries, for instance, or which pile of M&Ms is larger. This math sense is an important foundation for developing more advanced math skills later on.

In pre-kindergarten, children should learn to count to 20; identify shapes such as circles and triangles; and know relative words including “big,” “small,” “tall,” and “short.” By the end of kindergarten they should be able to count to 100; write numbers from 1-20; and know words such as “above,” “below,” “flat” and “solid,” according to the Common Core State Standards.

Math and Science Guidelines for First and Second Grades

A textbook alone isn’t enough. Look for plants and animals in the classroom. |

In first and second grades, children should be learning to add and subtract. They need to understand the value of coins, learn how to tell time, and know how to measure distances.

Look for a math area in the classroom with things such as dice, play money, dominoes, and number lines. Also look for counting frames, clocks, pattern blocks, and rulers. Well-equipped classrooms have, for example, “manipulatives”—little plastic cubes kids can snap together to learn to add and subtract.

Look for bundles of sticks used to represent “tens” and little cubes used to represent “ones” to help young students learn place value. Such tools help children understand the concepts underlying arithmetic, not just the rules for addition and subtraction. Classrooms often have a shelf with puzzles and games such as Sorry or Connect Four, which are fun ways for children to reinforce arithmetic skills, especially when they are indoors a lot during a long winter.

Children are learning to talk about math and read word problems at this age, so look for lists of math words posted on the classroom wall to help them remember words including “sum” and “difference.”

According to the Common Core State Standards, by the end of first grade, children should be able to add and subtract numbers up to 20; by the end of second grade, they should be able to add and subtract large numbers.

Math and Science Guidelines for Third Grade

Did you spy cooking ingredients and other kitchenware in your child’s classroom? Those are evidence of science exploration, too. |

In third grade, children learn multiplication and division. They need quick recall of math facts, so some drill is necessary. Look for worksheets, flashcards, and workbooks so children can practice basic math facts until they become automatic.

Children also need to understand what multiplication and division really mean. For that, teachers may ask children to color rows of squares on graph paper, or to cut strips of paper a certain width and length.

Third-graders learn to calculate the area and perimeter of a rectangle. Sometimes classrooms have square plastic tiles that children can assemble into rectangles so they can see concretely what area and perimeter mean.

Are the desks in rows? That probably means the teacher does most of the talking. But research shows kids understand math better if they talk about it and try different ways to solve problems. If you see desks in groups, it may mean children work on problems together—and that’s a good sign.

By the end of third grade, children should have memorized the times tables up to 10 x 10 as well as division facts. They should also be able to calculate the perimeter and area of a rectangle, according to the Common Core.

Math and Science Guidelines for Fourth and Fifth Grades

Look for a variety of science tools on classroom shelves, not hidden away in boxes. |

Fourth-graders need to be able to multiply and divide large numbers, and by fifth grade children should be able to multiply and divide fractions. You might see posters with drawings of problems such as: How can 8 children share 5 hero sandwiches fairly?

You may see charts showing the work kids have done to solve big word problems that require them to use all of their math skills—addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and fractions. If children solve problems in different ways, that’s a good sign that they understand what they are doing and have not merely mastered a formula.

Research shows children need both a deep understanding of math and the ability to solve arithmetic problems quickly, so look for evidence of both teaching approaches in the classroom. Numbers lined up in neat rows—the way most of today’s parents learned arithmetic—show a quick and efficient way to solve problems. Conversely, children’s written explanation of their work—part of most lessons today—is designed to demonstrate that they get the concepts.

Math textbooks are fine, but good teachers draw on several different math programs or resources (think instructional YouTube videos or sites such as Engageny.com, which offers an array of activities as well as games for helping students practice key skills of the Common Core State Standards) because not all kids learn in the same way. Some kids look at numerals on paper and understand them right away; others need pictures and objects to make sense of arithmetic. Some prefer worksheets and workbooks. Others need to count, use number lines, or use a computer. It’s helpful if there is variety. No one set of math books works for all kids; many of the best schools use elements from a variety of math books.

One of the best things we can do as parents is to be aware, interested, and open. Learning math and science is a process. Keep an eye on these classroom clues and grade-level milestones, and take note of how your child learns best. In Part 2 we will address more specific ways to support your child and to fill in the gaps in math and science.

Clara Hemphill, founder and senior editor of Insideschools, is the author of New York City’s Best Public Elementary Schools: A Parents’ Guide. Lydie Raschka, a writer at Insideschools, is a former public school teacher and a graduate of Bank Street College. Insideschools.org is a project of the Center for New York City Affairs at The New School.

Read part 2 for data and tips on how much time is (and should) be spent on test prep, what to ask the teacher in your next parent-teacher conference, and other proven ways to help your child succeed in science and math if your school falls short.

Also see:

Common Core Resources for Parents

How to Personalize Your Child’s Learning at Home